From Blacksmiths to Mechanics: Adapting to Survive in the Modern Age

As the sun casts its first rays upon modern city streets, humanity finds itself grappling with a dilemma that spans centuries: how do we adapt to a world that changes faster than our imaginations can fathom? On one hand, we have the historic social stratification that has shaped our civilizations,

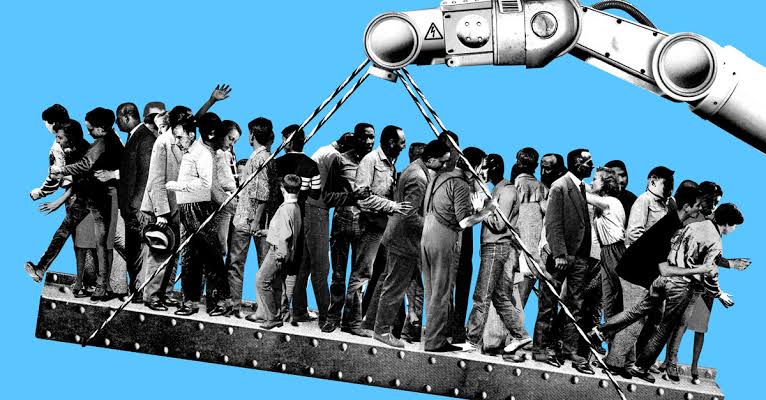

As the sun casts its first rays upon modern city streets, humanity finds itself grappling with a dilemma that spans centuries: how do we adapt to a world that changes faster than our imaginations can fathom? On one hand, we have the historic social stratification that has shaped our civilizations, from the first settlements to the zenith of the Industrial Revolution. But now, on the cusp of the 21st century, we're entering an era where the digital divide and the rapid rise of artificial intelligence present a fresh, unfamiliar concern – the threat of becoming obsolete.

This isn't merely a matter of statistics or a straightforward economic indicator. It's a human concern, a question of heart and soul. What becomes of those who find themselves in a situation where their valued skills and experiences, honed over years, are now deemed outdated or even superfluous? Are those dubbed the "unnecessary class" truly redundant, or do they still have a role in our increasingly digitized society?

In this article, we'll delve deeper into the heart of this issue, seeking answers to questions that concern us all. We'll explore how members of the "unnecessary class" can find their place in the sun, how they can re-educate and discover new opportunities in an era that prizes technological savvy more than ever. We'll move beyond fears and uncertainties, searching for inspiration and hope for those who might feel lost amidst the digital revolution.

Navigating the New Age: Hope for the 'Unnecessary' Class

In the shadowed halls of history, we find the blacksmith hammering away, crafting tools that would forge civilizations. Today, in the light of our digital era, the modern equivalent - the mechanic - tinkers with the machinery that propels our society forward. But as the horizon of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) age looms, what is the path for those who risk obsolescence? Historian Yuval Noah Harari’s unsettling prophecy hints at an emerging "unworking class," born from AI's omnipotence. The paradigm is shifting, and the imperative to adapt has never been more pressing.

The tale Harari paints is not a new one, but its contemporary canvas is. Just as mass industrialization once fathered a working class, AI's rise threatens to orphan a significant fraction, deeming them "unnecessary" in the grand scheme of things. Harari provocatively asks, "What should we do with all the superfluous people?" when non-conscious algorithms outclass human competence.

He dismantles the romantic idea that there will always be something inherently human that machines can't replicate. Drawing on biology, he posits that all organisms, including humans, are algorithms, sculpted by the meticulous chisel of evolution. Furthermore, algorithms don't care about the material they run on – be it organic brains or silicon chips. With this perspective, the distinction between humans and machines blurs, giving credence to the fear of human obsolescence.

Harari's assessment is hard-hitting: 99% of human qualities are redundant for modern jobs. As AI evolves, not only are they becoming adept at tasks previously deemed impossible for them but also humans, in specializing, are making it easier for machines to replace them. What happens then to the masses of people rendered obsolete?

We are staring at an inflection point reminiscent of the Industrial Revolution's societal upheaval. During that era, socialism burgeoned as the answer to the newly formed working class's concerns. Today, as AI threatens to spawn an 'unworking class,' who, unlike the unemployed, will be unemployable, we grapple for solutions to prevent societal fragmentation.

The projections are daunting. Research from Oxford suggests that by 2033, 47% of US jobs are at high risk of automation. Telemarketers, chefs, waiters, and even sports referees might find themselves in the annals of job history. But all is not gloomy. There is a tiny glimmer of hope for professions that demand sophisticated pattern recognition and aren't lucrative enough to warrant automation, like archaeology.

Harari rightly points out that the challenge isn't merely about creating new jobs. It's about forging jobs that humans can do better than algorithms. And in this evolving landscape, continuous learning becomes paramount. The traditional life arc of learning followed by working is dissolving. Lifelong learning and reinvention will be the new norm, and not all might be equipped for it.

Yet, it's essential to remember that every epoch of change has also been one of adaptation. As the blacksmiths of yore found new avenues in the face of industrial mechanization, so too can today's threatened professions. The impending technological affluence might well be able to sustain people, even if they aren't contributing to traditional work. But the question remains: what will give their lives meaning?

Harari suggests a retreat into virtual worlds, drugs, and computer games. But this paints a bleak picture that undermines human potential and spirit. As much as this is a challenge, it's also an opportunity – to recalibrate what we value, to re-imagine education, to rekindle the human spirit in the face of automation.

In the wake of this looming AI age, let us not be paralyzed by dystopian prophecies. Instead, let's channel the spirit of the blacksmith and the mechanic. Let's adapt, innovate, and above all, remember that our humanity, with all its creativity, empathy, and resilience, is our greatest asset.

As the gears of time turn, and the shadows of AI grow, the message is clear: To survive, one must adapt. From the era of blacksmiths to the age of AI, this remains our perennial challenge – and our enduring strength.